The world is facing a water crisis. WaterAid estimates that 785 million people don’t have access to clean water and that by 2040, 1 in 4 children will live in regions where water is severely scarce. Access to safe water and sanitation are a human right, and yet approximately 1 in 10 people don’t have access to clean water close to home, and 1 in 4 people don’t have access to a toilet of their own. Water, sanitation, and hygiene, referred to collectively as WASH, is critical in improving global health and wellbeing and wider socio-economic impact.

Commonwealth Alumnus Chilufya Chileshe is the Interim Global Policy Director for WaterAid, an international non-governmental organisation with the goal to make clean water, decent toilets, and good hygiene normal for everyone, everywhere within a generation.

Facilitating and sustaining change

In her role, Chilufya leads WaterAid’s global policy agenda to make WASH services accessible to everyone everywhere. Working in several countries, Chilufya, and her colleagues in WaterAid champion pro-poor WASH policy across a range of areas, from innovation and programme delivery, policy development, governance reforms, and citizen participation. Working across countries, Chilufya and her team must consider a range of factors in how support and services can be deployed and sustainably managed.

“We try and consider how change happens at the national level. What role can we play and facilitate that change in ways that are favourable to poverty eradication and particularly, access to water and sanitation as a key marker of that progress? … what kind of things need to be in place at a regional level to facilitate that national change. And then also looking at what kinds of global access and global processes will support policy change or policy implementation and success in favour of particularly the most vulnerable communities in the countries we work.”

WaterAid drives several large- and small-scale programmes and water supply and sanitation projects globally. Understanding the context and needs of each country is critical in identifying the best solutions and technologies to maximise impact. Measuring the impact of interventions can be multi-layered and is a key focus for WaterAid. For example, introducing a borehole and a piped water scheme in a particular area can be measured by the number of people who can access the water from taps, or children accessing toilets at their school. The longer-term impact and sustainability, however, relies on strong local governance and national monitoring to ensure continual operation and maintenance.

“[T]he things we believe are foundational to larger scale systemic change relate to governance processes that make sure that those services can be sustained. For instance, that water will continue to flow and that at the first sign of trouble, when a tap breaks down, it’s not abandoned.”

WaterAid have developed various ways to measure impact. One focused on the policy influencing work of the organisation, using the framework Planning, Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting (PMER). Chilufya was part of a team which developed this framework, which focuses on four areas which can be used to indicate if impact or change is being achieved. Using these areas, teams can assess a range of measures, including whether the right level of awareness is being created amongst policy makers, evidence of country level reform of policy or policy development because of their work, and the extent to which policies are implemented and serving their purpose.

Newly constructed bathrooms at a school in rural Malawi

The State of Hygiene: A review

Before her current role, Chilufya was the Regional Advocacy Manager in Southern Africa. In response to the limited attention to hygiene Chilufya initiated a review called the State of Hygiene in southern Africa. It focused on 10 countries in the southern African region, six of which WaterAid were already active in, and assessed the policy environment for hygiene. This involved gathering information on existing policies related to hygiene, where they existed, which aspects of hygiene these focused on, whether these where financed and implemented, and whether the institutional set-up to deliver policies was appropriate.

The review enabled the organisation to identify policy recommendations on areas that required change and highlight gaps. One gap was the absence of leadership on hygiene, due to its underrepresentation and therefore lack of understanding on this element of WASH more broadly. Following the review, the regional economic bloc, Southern African Development Community (SADC), agreed to instigate a regional instrument through which member states would commit to take action to improve hygiene. In March 2020, it was agreed with the Social and Human Development Unit at SADC that a regional hygiene strategy should be produced, and meetings are ongoing with a range of stakeholders to facilitate collaboration and implement a plan that will address hygiene needs across the region.

“The decision to spotlight hygiene, to drive a policy or advocacy agenda around that… is one of my points of pride. When we realised that we focus on water, sanitation, and hygiene as an organisation, but we hardly did enough on hygiene.

“It ended up being quite powerful in terms of our advocacy in the region, helping us to speak to various audiences, giving us chance to influence a greater focus on hygiene.”

Chilufya notes that the COVID-19 pandemic has changed people’s understanding of the importance of good hygiene practices and commitments at the government and policy level to ensure access to necessary hygiene services. Despite this, responses to the COVID-19 pandemic have highlighted where greater awareness and understanding of WASH is still required.

“I think we’re getting greater recognition of the need for water and toilets overall, but frankly the money to make this happen is still not flowing to the extent we need it to.

“[W]hen countries have finite resources to respond to the big, big problems, they very frequently choose the things that feel obvious and visible or close and immediate. Whereas WASH has long-term effects, and sometimes its outcomes are seen in the long term, makes it sometimes a little bit difficult to attract investment. That’s one challenge that remains, even now when the awareness and visibility of hand-washing, is high, we still don’t see the money that is required to drive the change at the scale necessary.”

Such change would include access to working hand-washing stations, access to soap, and working, hygienic toilets.

Climate change and the water crisis

Securing the funding required to drive WASH projects and reach the targets outlined in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6, which seeks to ensure access to water and sanitation for all, can be challenging. Chilufya shares that a recent WaterAid study shows there is an estimated financing need of USD229 billion per year for countries to meet the expectations of SDG 6. Identifying ways to finance this gap and the key stakeholders to support this agenda has led WaterAid to look at other financing models and ongoing work designed to contribute to achieving the SDGs and how these may support WASH initiatives. Climate action offers one such opportunity.

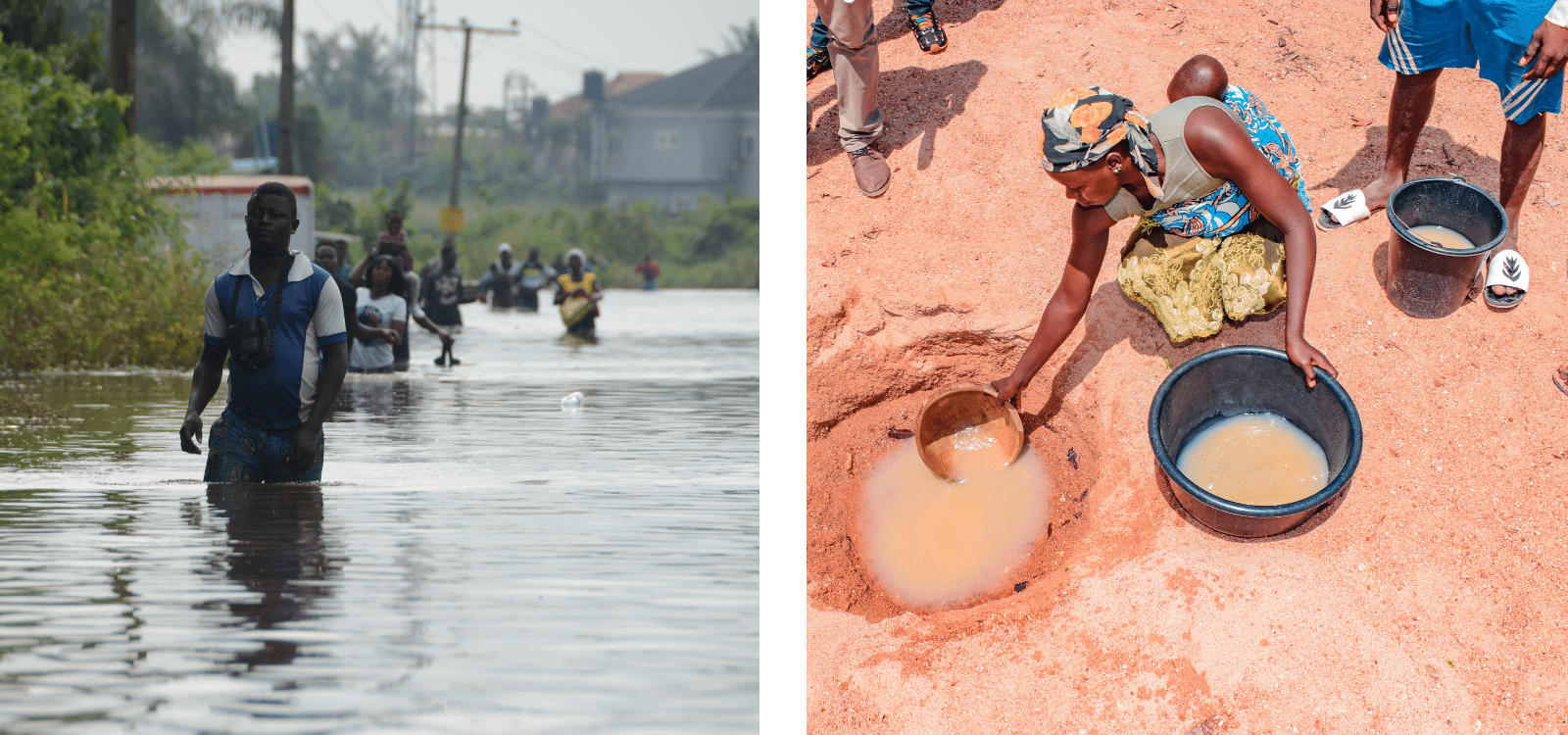

Climate change is a significant contributor to the water crisis. Increasing natural disasters in the form of floods, hurricanes, drought, and other weather-related events has resulted in the loss of water resources, contamination, and the displacement of millions of people, leading to increasing pressure to deliver vital WASH services.

“We often hear that many communities experience climate change as a change in water. Either they have too much of it, flooding and storms and hurricanes, or they have very little of it, droughts. When it’s a change in water, communities are basically left with no water or too much water, but it’s contaminated and therefore not available to them.”

WaterAid launched the Water and Climate Finance Initiative focused on the change required to ensure that climate finance is used to support highly vulnerable populations living without access to water and sanitation and develop resilience in communities. The initiative, The Resilient Water Accelerator, brings together a range of partners to support with project preparation funds which will enable climate projects to include a significant portion of water and sanitation development alongside the climate focused work. Chilufya believes this approach will ensure that, as communities experience the effects of climate change, they will be resilient to how this will change access to water.

Chilufya’s motivation

Contributing towards and driving positive change has been an important factor in Chilufya’s career to date. Prior to WaterAid, she worked for an organisation supporting citizen participation in local and national governance in Zambia. Being able to complete her MA in Public Administration – International Development at the University of York supported by a Commonwealth Distance Learning Scholarship enabled Chilufya to continue her work and directly apply her learning to real-life examples. Chilufya credits her studies for developing critical communication skills, including communicating complex ideas in simple and compelling ways.

“…I kept saying how interesting it was that every time I was doing a module, there was actually a real-life thing going on, either in my work or related other interests that was almost always related to what I was studying.”

As well as her work at WaterAid, Chilufya is the board chair for the Open Society Initiative in Southern Africa, part of the bigger Open Society Foundation, the world’s largest private funder of independent groups working for justice, democratic governance, and human rights. In this role, Chilufya is involved in critical thinking and responses to human rights challenges across the region, including rights for women, LGBTQI, and expanding the practice of democracy and civic action.

“I sometimes think of it as my life’s calling, to use the skills I have to help contribute to making our world a better place. I’ve been convinced about this from as early as I can remember.”

Chilufya Chileshe is a 2013 Commonwealth Distance Learning Scholar from Zambia. She studied for an MA in International Development at the University of York.