Commonwealth Alumnus Ving Fai Chan shares his experience and results on building training programmes and centres to deliver basic eyecare in low-resource settings.

Blindness and vision impairment affects at least 2.2 billion people around the world according to the WHO World Report on Vision 2019. Of those, 1 billion have a preventable vision impairment. Despite the importance of eye health globally, in many countries eye health is still not part of national health plans and does not receive sustained funding. Instead, several countries rely on NGOs to deliver short-term eye health programmes and interventions, resulting in limited coverage or passive eye health seeking behaviour.

Understanding and researching the needs of countries in relation to eye health programmes, thus plays an important role in identifying appropriate and sustainable approaches to combatting preventable blindness and other treatable eye diseases.

“I think eye health in general has been slowly gaining attention since 1999, when ‘VISION 2020: The Right to Sight’ started” Ving Fai says, in reference to the global programme launched by WHO and International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness. “People also now understand that improved vision is very closely related to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), for example, improved health, improved wellbeing, improved work productivity. That’s why we reduce poverty, improve education, and so much more.”

Eye health plan for a war-torn country

Following the completion of his Commonwealth Shared Scholarship in 2009, Ving Fai joined Australian eyecare NGO, the Brien Holden Vision Institute (Africa) Trust (BHVI), based in South Africa, where he took up the position of lecturer. For his first assignment, he was based in Eritrea and was tasked with developing a national human resource for eye health plan, with the aim of training optometry diploma graduates to provide basic primary eyecare. Eritrea won independence from Ethiopia in 1993 after a 30-year war. The prolonged conflict impacted the country’s development. At the time of Ving Fai’s posting, national services in Eritrea were under development, which gave Ving Fai and his team a blank canvas to work with, a blankness emphasised by Ving Fai’s stats about the country.

“In 2009, it [Eritrea] was reported for a population of around 5 million people, there were less than ten eyecare personnel.”

To improve access to eyecare, Ving Fai’s plan introduced a two-year training programme for optometry diploma graduates to qualify them to deliver basic eyecare, which in most cases can be the determining the prescription and dispensing of glasses. They were also trained to diagnose severe eyecare problems, which would then be referred to more qualified eyecare personnel for treatment.

Whilst the plan focused on the training and deployment of graduates, there were no established government posts for them to take up. As such, although primarily an education programme to build skills and training, Ving Fai worked closely with the Ministry of Health to create positions for these graduates across Eritrea. This included the development of local vision centres, where graduates would be based to provide services at community level. The plan also included the establishment of an optometry school to enable future studies and provide clinics.

By 2012 when Ving Fai left the project, 60 graduates had been trained to deliver basic eyecare, an optometry school was established to provide clinics, as well as four vision centres based in different areas of Eritrea. Vision centres now, apart from offering glasses prescriptions, are also treating minor eye diseases, such as conjunctivitis, if the technician is supervised by a senior clinical officer (for example, an ophthalmologist, ophthalmic officer, optometrists, experienced nurse).

Ving Fai believes taking up this role just two months after completing his Scholarship at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) played an important part in implementing the skills and knowledge gained during his studies.

“The MSc Community Eye Health course focused a lot on programme planning, programme development, and focused a lot on understanding how you monitor and evaluate the programme that you put in, and also a big component of management. With those three sets of very important skills, going straight into the field, I think that really helped me a lot.”

Building a team

In 2012, Ving Fai was promoted to research manager at BHVI and returned to their headquarters in South Africa. At the time, the research department was new and Ving Fai took the opportunity to develop a strategic plan for the research group and built a team of six permanent researchers from a range of backgrounds, including social science, statistics, data collection, and management.

Over the next seven years, under Ving Fai’s management, the research group conducted studies across Africa, including in Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Zanzibar, and Malawi. The group also expanded their work to other parts of the world, such as South America. By 2018, the group had completed 12 research studies and received approximately £1 million in research funding from multiple funders.

Creating Vision Champions

Vision Champions, a key project Ving Fai has been involved in began as a pilot in the Bariadi District in rural Tanzania. Its aim is to improve people’s eye health awareness and knowledge, and to improve eye health practices more generally.

In researching the best approach, Ving Fai and his team observed high numbers of children in rural areas and felt they could play an active role in the project. Many children in low and middle income countries, including in rural areas, are the first generation in their household to receive some form of formal education. The team had the idea to create a peer-delivered education strategy. Under this approach, children would be given the tools and knowledge to share information on eye health within their community.

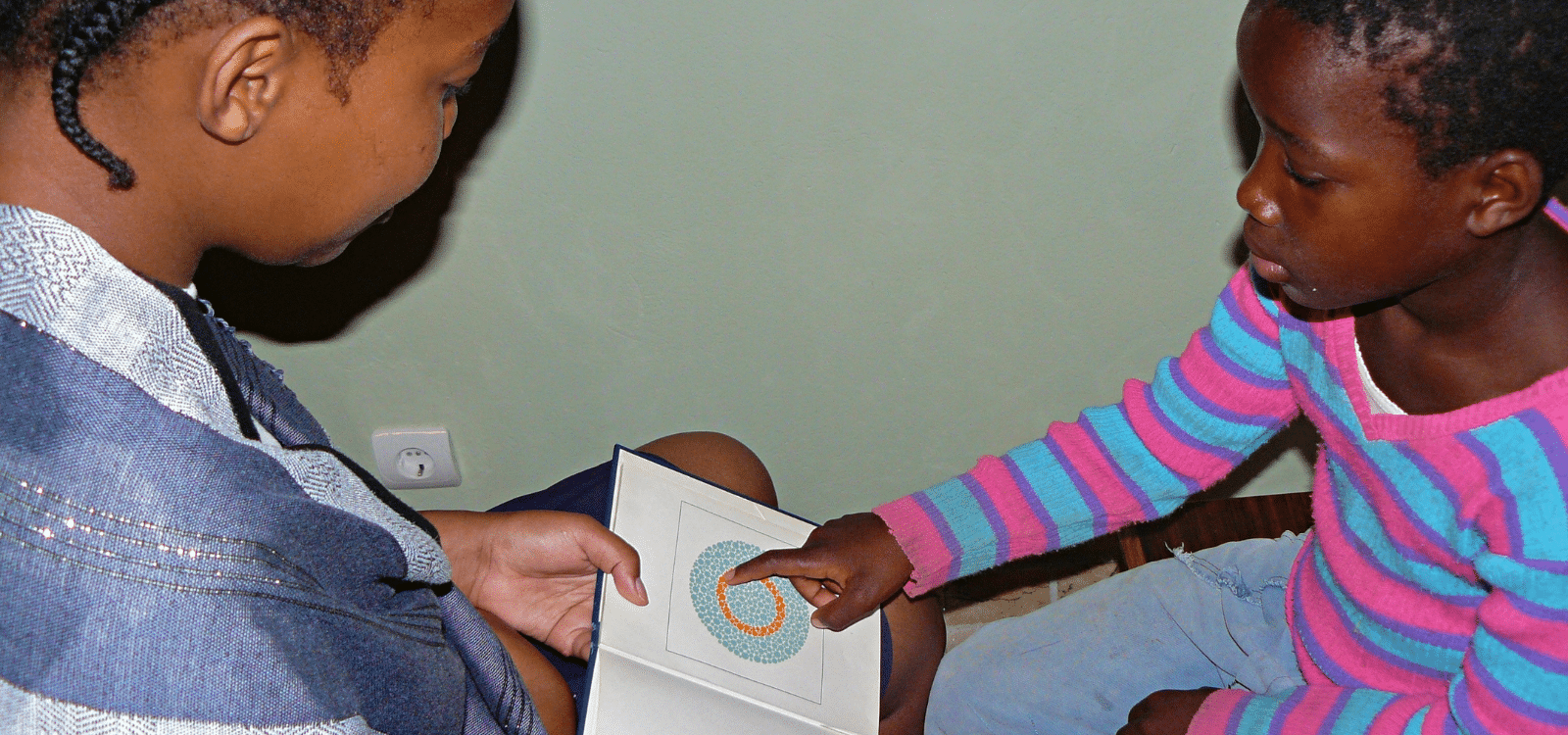

To make the delivery engaging to children, the team decided to use comic booklets to deliver key messages and set up community engagement opportunities for children to provide comments on the draft booklets and how they would like information to be portrayed. As well as general eye health information, the comic booklets also included an eye screening activity they could deliver.

“At the very end of the comic booklets are very small, what we call, eye screening charts, so that they can screen the vision of their friends at school and also their family. And if they found that someone can’t read that reading card, then they will have to be referred to the eye clinics.”

By the end of the pilot, Ving Fai and his team had trained over 120 children, now referred to as ‘Vision Champions’. Their enthusiasm for the task resulted in their sharing stories and information to over 6,000 people, including family and friends. As a result of the pilot, more than 2,000 children and their family members were screened and the number of people going to the eye clinics increased by almost 200%. The positive impact of the role young Vision Champions made in their community did not go amiss with Ving Fai.

“It just shows that children, sometimes we underestimate their ability.”

Whilst the increase in visitations was a positive outcome, it resulted in patient congestion at eye facilities, despite working with the local hospital and eye clinic managers. Following its success, the pilot has been adopted in the East Africa Child Eye Health Programme in Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania. The International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (IAPB) have also used the case study in their Standard Guidelines for School Eye Health programmes.

Ving Fai notes that in relation to this, one of the biggest challenges in his work is the lack of data to support realistic planning. In another implementation research project in Zanzibar, there was no data available for planning. Hence, data from Tanzania and other nearby countries was used to estimate the project’s potential outputs, resulting in an underestimation for Zanzibar. A positive outcome is that there is now data available to support future projects.

Turning research into action

Research is an important part of developing appropriate eyecare plans or interventions and in assessing the maturity and readiness of a country to adopt and implement them. Countries often face different challenges in implementing eye health programmes and therefore different approaches are required. For example, projects delivered by Ving Fai in Malawi, Uganda, and Eritrea required human resource interventions, with research focused on the number of eyecare personnel and the impact of the programme in this area. In other countries, his research has focused on the implementation of eye health programmes and health promotion strategies.

Turning research into an intervention is no easy task, however, and faces its own challenges.

“A lot of [the] time you will see that research is mainly conducted by academia or by academic institutions, whereas a lot of implementation is either done by ministries, NGOs, or charity groups. Even though today we see a lot of collaboration between the two groups, when I first started in 2009, it wasn’t easy because the crossover wasn’t that obvious at that time.”

Another challenge is the timeframe allocated to conducting research, developing, and implementing a project or intervention, and collecting data to evaluate and report back on impact. With limited funding periods, expectations amongst stakeholders for how much time and resource should be allocated to research and its implementation can become mismatched. In these cases, Ving Fai believes staying focused on the end goal of the programme, despite different opinions and perspectives on the programme delivery, is key to achieving the aims and objectives, and collaborating effectively.

This was particularly important for a project Ving Fai delivered in Zanzibar in 2017. Funded by the USAID Child Prevention Blindness Programme, Ving Fai worked to assess the benefits of integrating an eye health programme into an existing school health programme. The project brought together a range of stakeholders, including the Ministries of Education and Health in Zanzibar, NGOs working in eye health, NGOs working in nutrition, and academic institutions in Tanzania and the UK.

Changing the approach

Ving Fai believes that a change in approach may be needed.

“A question that a lot of policy makers will ask is that since the traditional way of doing it works, why do we need to change the approach to an integrated approach? Well, the idea that we have is that while a vertical programme may work in short term, because it is so reliant on funding, perhaps an integrated approach will be more sustainable […] So what we need to prove is that if we are going to integrate school eye health into a school health programme, the performance must either be the same if not better, and the cost effectiveness must be higher in the integrated way of doing it.”

Through the integration of the two programmes, within six months the team screened over 11,000 children and the cost effectiveness was twice that of running two separate programmes. Based on this initial success, a child health forum in Zanzibar has been established to support the advocacy for wider integration programming.

One major outcome of this project concerns health promotion. Despite the cost effectiveness of the integrated model, spectacle wear and compliance are still very low amongst school children. Whilst a health promotion programme was included in the project, the chosen delivery method, through posters and leaflets, has proven to not be very effective for several reasons including low perceived relevance amongst their target audience and accessibility of content amongst those with lower education levels. This has led to a new project, Zanzibar Arts for Children’s Eyesight, (ZANZI-ACE), which will integrate the arts into eye health strategy and health promotion.

A global contribution

In 2018, Ving Fai took up the position of lecturer in Global Eye Health and is part of the Health System Research Group at the Centre for Public Health, Queen’s University Belfast. Alongside lecturing to master’s students in public and global health, he continues to contribute to research into improving access and quality of eyecare services in low-resource settings. Countries he is currently working in are Nigeria, South Africa, and some work in India and China.

In 2019, he was appointed as an Honorary Lecturer at the University KwaZulu Natal, and in 2020, was appointed as a Trustee of Vision Aid Overseas, a UK-based eyecare NGO and the Research Advisor of the Tanzanian Optometry Association.

With expertise in both project implementation and research, and with increasing collaboration between researchers, funders, and implementors to deliver interventions, Ving Fai believes the work of public health and global health specialists is becoming increasingly important in achieving public health goals.

“One of our biggest roles is bridging that gap [between researchers, funders, and implementors], especially people from my background who have a mixture of research and implementation; you have an understanding from both groups. What are the academics looking for, and what are the implementers working for? A lot of time, you are in the middle, and you try to communicate.”

Ving Fai Chan is a 2008 Commonwealth Shared Scholar from Malaysia. He studied for an MSc Community Eye Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.