Human rights in relation to sexual orientation and gender identity are a pressing issue across the Commonwealth. Due to the colonial legacy of homophobia, anti-LGBT legislation and discrimination of the LGBT+ community is significantly over-represented in the Commonwealth group of nations where 59% of countries criminalise homosexual activity compared to 34% globally.

Due to these attitudes and laws, people who are LGBT+ are at a higher risk of experiencing hate crimes compared to heterosexual people and are more likely to experience mental health problems, such as depression and self-harm.

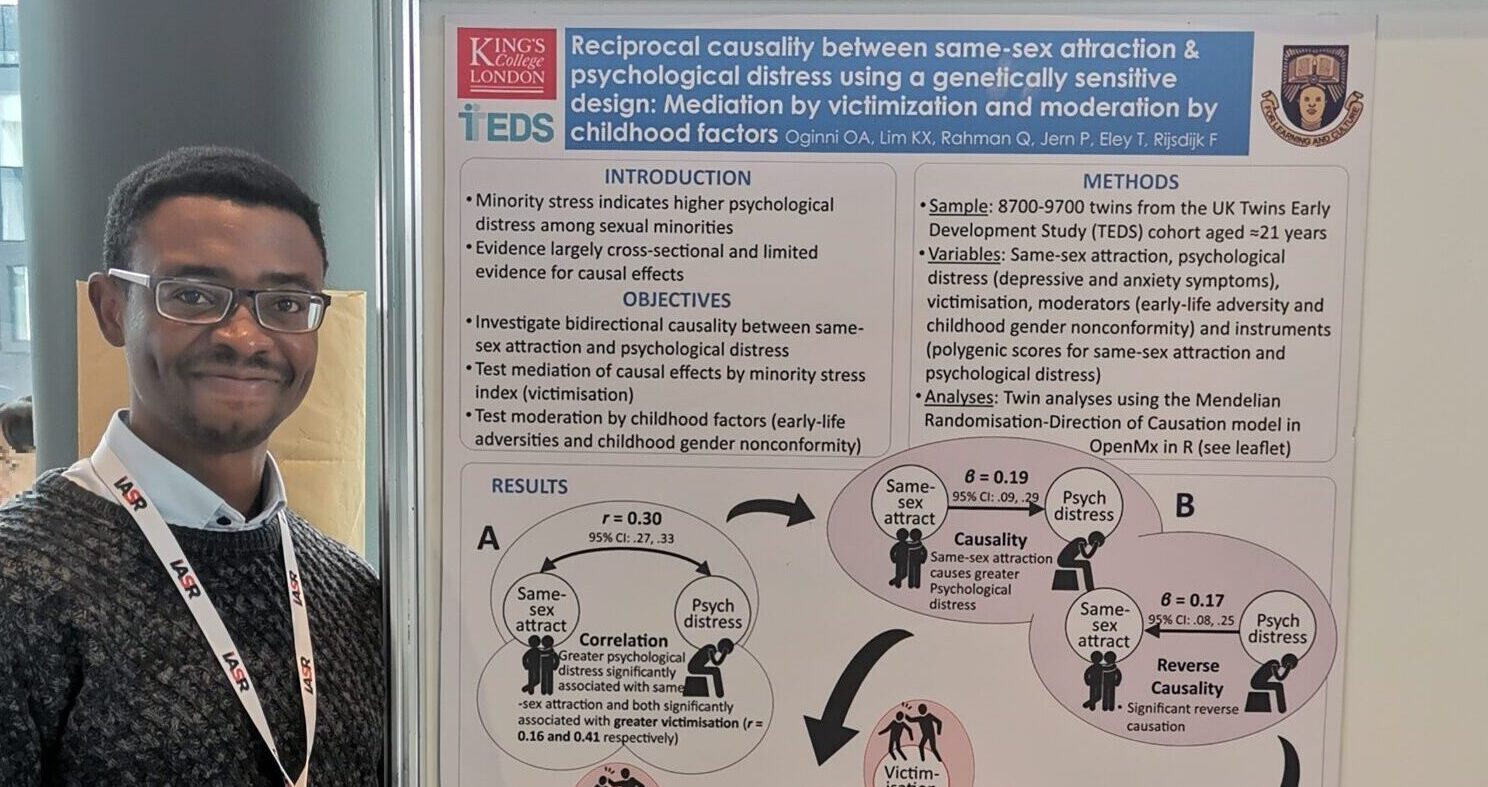

Commonwealth Alumnus Olakunle Oginni is a lecturer at Obafemi Awolowo University and a consultant psychiatrist at the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex (OAUTHC) in Nigeria. His CSC-funded doctoral research investigated the relationship between sexual orientation and adverse mental health to better understand the experiences of LGBT+ people and appropriacy of existing mental health support.

Establishing the link between stressful environments and psychological distress

During his residency training at the OAUTHC, Olakunle observed that the rates of depression and suicidal ideation amongst male students who were gay or bisexual was three to four times higher than their heterosexual counterparts. Following this observation, Olakunle wanted to understand the links between mental health issues and LGBT+ people and identify ways to address these.

During his Commonwealth Scholarship, Olakunle further developed expertise in twin modelling and behavioural genetics. Twin studies consider similarities observed between identical and non-identical twins, with the logic that identical twins are nearly 100% genetically identical. Where different traits are identified between these individuals, further investigation can be applied to understand whether differences are due to genetic factors and non-genetic factors.

Olakunle applied this approach to investigate whether the stress associated with sexual orientation was the cause of psychological stress and adverse mental health, or if common genetic factors influenced their mental health.

His studies revealed there was no genetic link between LGBT+ individuals and adverse mental health and that non-genetic factors were the cause of psychological distress. However, exploring his findings further, Olakunle showed for the first time that psychological distress experienced by LGBT+ people reinforced experiences of stress associated with identifying as LGBT+ (also known as sexual minority stress).

“[This] was the first time anybody found that. And the implication is that it’s not enough to design interventions at the public level to reduce stigma. At the individual level we need to look at how psychological distress may reinforce sexuality related stress.”

The case for interventions that support LGBT+ people

Olakunle’s findings are important on several levels. Understanding that non-genetic factors influence the mental health of LGBT+ people means that interventions can be developed to limit or prevent these external factors, such as changes in laws and societal attitudes, but also that more comprehensive mental health support needs to be provided at the individual level.

He notes that existing interventions, such as inclusive policies on gender and sexuality in countries like the United Kingdom and United States, are validated by his findings. In supporting individuals, Olakunle feels that more needs to be done to train therapists in supporting LGBT+ people with mental health concerns.

“If the therapist is not well grounded in LGBT mental health it may be easy to gloss over the difficulties that stem from being sexual minority… therapists should be aware of that association between minority stress and psychological distress.”

The wider picture of minority stress across the globe

The data Olakunle used to conduct his research was from Finland and the United Kingdom due to sensitivities of collecting similar data in his home country, Nigeria, and other neighbouring west African countries. Reflecting on how his findings can be applied to these countries, he shares:

“On the one hand, it validates the concept of sexuality related stress or minority stress that has also been demonstrated in Africa and many other low and middle income countries. So, to that extent I would expect that my findings may also be applicable to these settings.

“However, the other layer is that the minority stress in non-Western countries may be a bit more nuanced.”

To understand what these nuances may be, Olakunle cites European research divided between LGBT+ friendly countries and those with anti-LGBT+ legislation. This research investigated different forms of minority stress, such as self-discrimination and concealment of sexual orientation. Interestingly, in areas where LGBT+ stigma was high, individuals who chose to conceal their sexual orientation to avoid discrimination experienced lower levels of psychological distress, despite the stress caused by the act of concealment.

Olakunle stresses, however, that the severity of stigma varies from country to country and that more research is needed to fully understand the mental health experiences of LGBT+ people.

“We can’t just take findings from high income countries and translate them into lower and middle income countries.”

Embedding LGBT+ sensitive care within the medical profession

Currently, training in LGBT+ sensitive healthcare is not offered as part of medical and hospital training. As a lecturer and consultant psychiatrist, Olakunle looks out for opportunities to gain skills in this area to apply to his clinical practice and the training he provides to his students and hospital residents.

“I’m able to train resident doctors in asking the questions in the right way, in a way that LBGT patients do not feel discriminated against. And even though I get the sense that some of them have non-positive attitudes towards being LGBT, they are able to be neutral.”

More formally, Olakunle has applied his extensive research in psychiatry to contribute to incorporating genetics in the postgraduate psychiatry curriculum as part of Nigeria’s National Postgraduate Medical College Doctor of Medicine (MD) programme. The programme is a clinical alternative to a PhD and is undertaken by doctors as part of an increased call for clinicians to provide evidence of their competency as medical professionals and build research excellence at the university and national level.

Following his Commonwealth PhD Scholarship, Olakunle and a fellow researcher developed and delivered six lectures on psychiatry and genetic research for the MD which they hope to build on and expand in the coming year.

Improving understanding of twins’ mental health across the income divide

Looking to the future, Olakunle hopes to continue his research in twin studies and to develop a longitudinal twin cohort. His home region of Osun state in Nigeria has one of the highest rates of twinning in the country and a study of this nature would be only the third in a low and middle income setting. In particular, Olakunle would like to provide comparison data to similar longitudinal twin studies in higher income settings, with a focus on understanding the differences and similarities in mental health disorders amongst twins in low and middle income settings compared to high income settings.

Olakunle credits his Commonwealth Scholarship and studies at King’s College London with equipping him with the research experience and confidence to undertake this type of study.

“Looking at myself before and now, I feel more confident with research, I’m passionate about research. And I think that level of confidence has translated to other areas of my professional practice, clinical and so on. And one of the things I learned and I’m still learning, is collaborative research, working with other people in a group, to take on different perspectives.”

Olakunle Oginni is a 2018 Commonwealth Scholar from Nigeria. He completed a PhD in Behavioural Genetics at King’s College London.