Recognising the critical contribution of nurses and midwives globally, the World Health Organisation (WHO) designated 2020 as the first ever global Year of the Nurse and Midwife, also marking the bicentennial of Florence Nightingale, the founder of modern nursing.

On World Health Day 2020, the WHO released the report, State of the World’s Nursing 2020, in partnership with the International Council of Nurses and the global Nursing Now campaign, and with support from governments and other partners. The report presented a global overview of the nursing profession and stated that, without action, there will be a global shortfall of 4.6 million nurses by 2030.

Commonwealth Alumnus Augustine Asamoah is the Research and Evaluation Manager at the Ghana College of Nurses and Midwives. Here, he reflects on the last five years of his work at the College and shares the importance of research and evaluation in ensuring the effective and efficient training of nurses and midwives from across Ghana to improve and strengthen health services nationwide.

“Monitoring and evaluation has great potential for programme improvement and learning. You actually know what is working, what is not working, and it helps you create awareness about what these nurse education programmes can actually achieve at the end of the day”

The Ghana College of Nurses and Midwives was established in 2011 by an Act of Parliament (Act 833) with the mandate to train postgraduate specialist nurses and midwives at the Associate, Membership and Fellowship levels. In 2015, the College accepted its first intake of students to begin postgraduate studies in nursing and midwifery. In the same year, Augustine joined as a research and evaluation coordinator, tasked with developing a monitoring and evaluation (M&E) framework to assess the College’s teaching programmes, knowledge and skill acquisition amongst students, and improvement in skills practice in health facilities following the completion of training.

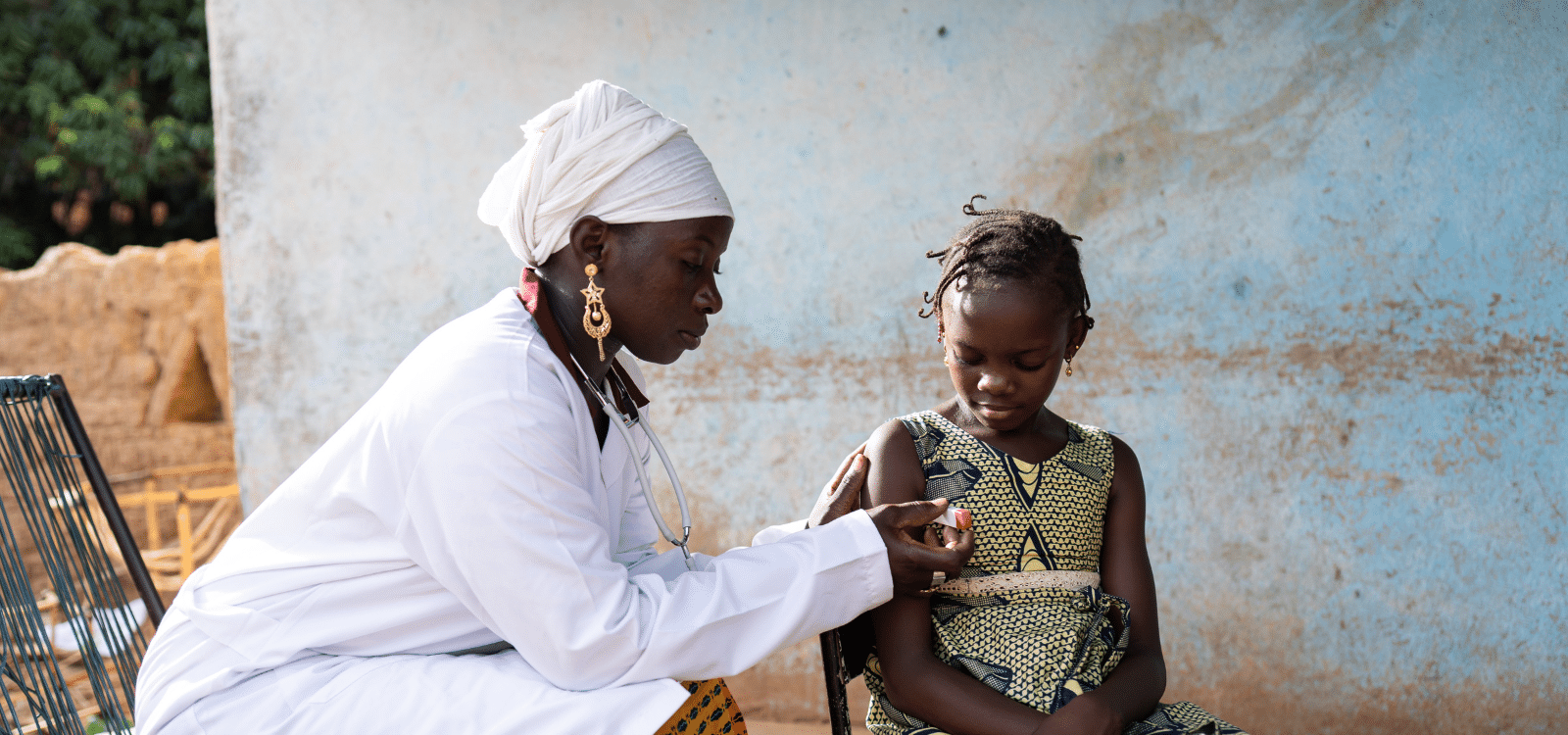

Augustine was part of the SickKids-Ghana Paediatric Nursing Education Partnership (PNEP) Programme at the College, which was funded by SickKids Foundation, Canada, and the Government of Canada. PNEP was a collaborative partnership between the Ghana College of Nurses and Midwives, SickKids Centre for Global Child Health, Canada, the Ghana Health Service and Ministry of Health. The overall goal of PNEP was to train 500 paediatric nurses from underserved districts and regions in Ghana between 2015-2020.

Prior to his work at the College, Augustine had held monitoring and evaluation roles outside of the public health sector, however he credits his Commonwealth Scholarship and MSc in Public Health at the University of Southampton for changing his use and application of evaluation data to inform improvements in public health training.

“The MSc programme at Southampton actually helped to shape my public health career and I am forever grateful for the opportunity!

“[W]hen I came back from Southampton, and I started this new role, I realised I didn’t actually understand most of the things I was doing [previously]. Currently, for the past five years, I’ve really understood what we mean by utilisation focused evaluation. What I mean by that is, we collect a lot of data and we use every bit of data that we collect.”

The key skills Augustine developed were in statistics and quantitative methods, SPSS, analysing quantitative data, and learning how to present this in clear and informative ways to stakeholders.

One example of this use of data is in recruitment. During the five-year programme, Augustine used demographic data to inform the College’s recruitment working group to ensure the selection of nurses and midwives from under-served districts and regions. Using data on nurses and midwives already enrolled at the College, or who had previously completed studies, Augustine worked with the team to identify eligible candidates from health facilities where staff had not already been trained and ensure spaces were given to those working in health facilities most in need.

“… we ensure that we reach saturation in each of these regions. We don’t want to be recruiting everybody from Accra, the national capital. Then you leave the other regions, especially the northern part, where we have high mortalities and morbidities when it comes to maternal and child healthcare.”

As a result of the PNEP programme, 501 paediatric nurses have been trained from 220 health facilities across all 16 regions of Ghana. Over 50% of the nurses were recruited from underserved regions and 99% of the graduates have remained in the Ghana Health System.

Statistics on the impact of the programme report an aggregate 37% increase in knowledge compared to baseline findings across all cohorts, a statistically significant change. Students reported an increase in confidence by the end of the PNEP programme, with the biggest increase in relation to physical assessment and history taking. Graduates have reported retaining competencies in key areas of paediatric care 14 months post-graduation.

How to assess quality

As a new College with 13 specialist programmes, including paediatrics, oncology, haematology, mental health, and advanced midwifery, it was important that Augustine develop mechanisms to assess the quality of teaching and programme content and its impact on knowledge and skills development amongst students, and their confidence in performing clinical assessments.

Augustine decided to adapt the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), an evaluative tool which can be used to assess healthcare professionals in a clinical setting. Adapting this tool to suit each programme enabled him to measure the improvement and practice of key clinical skills covered in programme curricula and formed a critical part of assessment and examination for students and teachers. Further M&E measures included the introduction of pre- and post-knowledge and confidence tests, based on curriculum content, to understand individual student learning over time.

As a means of validating and understanding the quantitative data collected, following the completion of each cohort, Augustine selected students based on a criteria such as type of facility, work experience, region, ward where nurses work, to take part in focus group discussions. Areas for further insight included what they felt went well over the course of the programme, challenges, and how prepared they felt to return to their parent facility and resume work. The information shared was then used to feed back into the programmes and advise changes.

For example, students reported they needed more support at the skills lab and during practicum at the clinical area. In response to this feedback, the College recruited more clinical educators at each training site to support clinical teaching, however this was not successful in all cases, with students reporting that they could not achieve their learning objectives at some facilities during the clinical practicum. Instead, students suggested the skills lab training should include demonstration of paediatric specialised equipment, such as how to set up and monitor Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP). This feedback was incorporated into the curriculum during the subsequent reviews to ensure they could meet their learning objectives.

Whilst implementing a robust M&E framework has provided the College and PNEP with information to improve and assess the impact of individual programmes and curricula, students also found this useful for their own personal and professional development, as they were also able to see how their skills and confidence changed over time. Augustine is pleased to report that in some cases, nurses intend to implement a similar M&E framework in their workplaces.

“Some of them even told me, when they go back, it’s going to be part of their routine clinical work at a facility level. At the end of the day, they will evaluate and see whether they have achieved their objectives, based on certain basic indicators that I taught them.”

Understanding impact

Augustine stresses that the benefits of the programmes are not just measurable at the individual or College level, but also within the institutions and facilities that students return to, the staff they work with, and their patients. In 2018, three years into the programme, he conducted key informant interviews at the post-training stage to understand the impact nurses and midwives were able to achieve following their studies.

Interviews were scheduled with 30 key informants representing the then 10 regions in Ghana. Key informants were selected from four categories; clinical informants, those who work with the nurses and midwives at the facilities; the graduates themselves; faculty teaching on the programmes; and health system informants, those who ensure the reintegration of graduates back into the healthcare system. This included the then Director General of the Ghana Health Service and the then Chief Director of the Ministry of Health, Paediatricians and Registrar of the Nursing and Midwifery Council of Ghana.

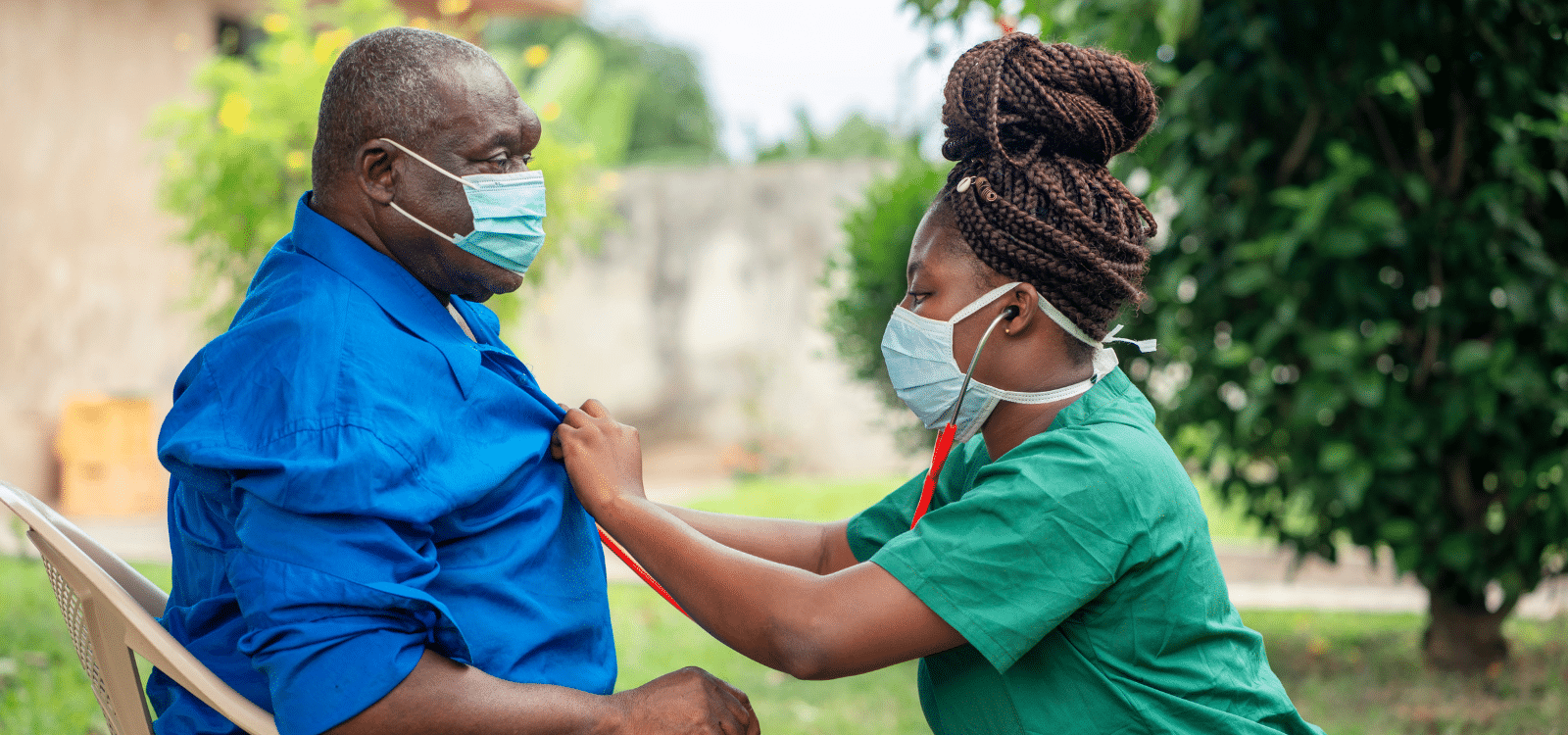

Findings from these interviews and the data collected has ensured that the impact of the College is realised at a number of different stakeholder levels. As part of the programmes, nurses trained in hospitals to develop their skills in real clinical settings and Augustine gathers performance feedback on changes and improvements that could be made at the facility level to both deliver the training and quality healthcare for the patients.

“At every point, each of these stakeholders are benefiting one way or the other from my M&E data and evidence.”

Responses gathered from key stakeholders as part of these interviews confirmed that the PNEP programme has begun to bridge a very important gap in access to child health services. Whilst progress has been made in Ghana in decreasing the rate of under-five mortality (from 72 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2012 to 51 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2016) the number is still high, especially given that the causes of death remain mainly preventable in this group. Several stakeholders confirmed paediatric nurses were “essential” in reducing this number and that given the shortage of paediatric nurses, the programme is valuable in “producing a critical mass of nurses” that can provide essential services, especially in underserved areas.

Clinical informants reported that the skills of returning graduates have enabled some facilities to expand their services to clinical areas that would not have been possible previously, thereby expanding access for patients and families in Ghana. It was also reported that post-training, graduates are initiating better and more comprehensive care sooner. For those who had attended the Associate programme, informants also noted a change in attitude towards their work, and utilisation of the concept of family centred care.

In his interviews with the graduate nurses, Augustine was keen to understand how they have integrated back into the health facility and if they have been given the space and support to implement their skills and achieve positive change.

“And the story has been great. They tell you, before I came to school, we were not doing A, B, and C. But when I went back, based on the knowledge and skills that I acquired, I am able to advocate for say, sickle cell or an IMCI unit for paediatrics to be established…[W]e’ve been able to train 501 paediatric nurses and deployed them into the facilities. And they are working, they are creating change everywhere.”

Looking to the future, he hopes to conduct an extensive impact evaluation of the programme to report the full success and challenges experienced by the graduates.

Working with so many partners meant Augustine had to balance several programme expectations and ways of reporting M&E results. With time, partners were able to work together to define expectations and develop protocols and report templates, using data visualisation to standardise approaches and produce reports that met the needs of the various stakeholders. Augustine attributes the strength of PNEP’s management to the success of the programme’s partnerships, creating space and opportunities for the program management team (PMT) to meet regularly and identify solutions to challenges as a team.

Increasing capacity through training

Drawing on his work at the Ghana College of Nurses and Midwives, Augustine’s work has shown the importance of M&E in improving the capacity of nurses and midwives and healthcare facilities. He has developed an M&E Department at the College and provided training and mentorship to colleagues to increase capacity. At the GHS and Ministry of Health level, he has introduced regular reporting and performance updates, allowing them to better understand the overall output and impact of the College programmes.

Augustine notes that M&E is still broadly new in Ghana, but positive changes have been made at the government level. With the establishment of a new Ministry for Monitoring and Evaluation and the introduction of mandatory M&E units in government ministries, agencies, and departments, including the Ministry of Health, Augustine believes a critical understanding of the need and importance of M&E to evaluate government flagship programmes and activities within the public sector has been realised.

Looking to the future, Augustine hopes to see increased recognition of the importance of M&E across more government programmes to inform government and citizens alike.

“I think it cuts across not only for the health programmes, it cuts across for every intervention or for every project or programme, even at the organisation or facility level. You need to track and monitor… I think when this government came and established a Ministry for Monitoring and Evaluation, it paved the way.”

Augustine Asamoah is a 2013 Shared Scholar from Ghana. He studied for a MSc Public Health at the University of Southampton.